Ferrous vs non-ferrous metals differ in magnetism, corrosion, and machinability. In sourcing and CNC machining, those differences show up as fixture choices, inspection risk, surface-finish stability, and whether a part survives humidity, salt, or chemical exposure without surprises. If you only compare “steel vs aluminum,” you can miss the real drivers that change total cost and quality. This guide gives you a clear decision framework, a buyer-friendly cheat sheet, and an RFQ checklist so you can choose materials that machine well, meet the environment, and quote cleanly.

Quick Decision Guide Start Here

If you want one simple rule: ferrous metals (iron-based) are usually chosen for strength, wear resistance, and cost; non-ferrous metals are often chosen for corrosion resistance, low weight, and conductivity. Then you refine the choice by the environment, magnetism constraints, and CNC machinability.

If you care most about strength and cost

Pick a ferrous material first (carbon steel, alloy steel, many stainless grades, cast iron) when you need:

-

High strength/stiffness for the size

-

Better wear resistance (often with heat treat or surface hardening)

-

Cost stability in common supply chains

Then confirm corrosion risk and finishing needs. If your design starts with carbon or alloy steel, these CNC steel parts examples show typical applications and machining routes. Unprotected carbon steel will oxidize in humid environments.

If you care most about corrosion resistance

Start with non-ferrous or stainless when the environment is harsh:

-

Outdoor exposure, condensation, or washdowns

-

Salt air / coastal conditions

-

Contact with chemicals

Aluminum and many copper alloys resist “red rust,” but they can still corrode in other ways. Stainless resists rusting better than carbon steel, but some conditions still cause localized corrosion.

If Magnetism Matters for Fixtures Sorting and Sensors

If you must have “non-magnetic” behavior, do not rely on “ferrous vs non-ferrous” alone.

-

Some stainless steels can be weakly magnetic or become more magnetic after processing.

-

Some non-ferrous metals (notably nickel) are magnetic.

If magnetism is a functional requirement, treat it like a spec item: define what “non-magnetic” means for your application and verify with a sample.

If you care most about CNC cycle time and surface finish

Many non-ferrous alloys (especially aluminum and brass) are easy to machine fast, but “easy” depends on:

-

Chip control

-

Burr control

-

Workholding stiffness (thin walls)

-

Surface finish expectations

Some ferrous alloys machine very well too (for example many carbon steels), but stainless and heat-treated steels can increase tool wear, heat, and cycle time.

What “ferrous” and “non-ferrous” actually mean?

Ferrous metals are iron-based. Non-ferrous metals do not have iron as the base metal. That’s it. The label is a family name, not a full engineering specification. When you actually source CNC parts, the decision lives at the alloy level—for example, 6061 vs 7075 or 304 vs 316—so it helps to start from a clear material list and then narrow by environment and machinability. You can use our materials overview for CNC machining to shortlist grades before you lock the RFQ.

Common Ferrous Metals Iron Based Examples

Ferrous metals include:

-

Carbon steels (mild/low carbon and higher carbon)

-

Alloy steels (chromium, molybdenum, nickel additions, etc.)

-

Stainless steels (iron-based alloys with significant chromium)

-

Cast irons (gray iron, ductile iron, etc.)

These materials cover a wide range of strength and machinability. Heat treatment and condition matter as much as “family.”

Common Non Ferrous Metals No Iron Base Examples

Non-ferrous metals include:

-

Aluminum alloys (common CNC choices for lightweight parts)

-

Copper and copper alloys (brass, bronze)

-

Titanium alloys

-

Magnesium alloys

-

Nickel alloys (including pure nickel and many high-temperature alloys)

-

Zinc (often used as die cast base metal)

Non-ferrous does not automatically mean “soft” or “corrosion-proof.” Titanium is non-ferrous and strong. Some copper alloys are quite hard.

A simple mental model: “family” vs “grade”

Use “ferrous vs non-ferrous” to narrow the conversation. Then switch to the real decision inputs:

-

Grade/alloy (example: 6061 vs 7075; 304 vs 316)

-

Condition (annealed, cold worked, heat treated)

-

Product form (plate, bar, tube, forging, casting)

-

Environment + finishing

-

CNC features (thin walls, threads, tight tolerances, surface finish)

Magnetic Properties of Metals What Is Magnetic and What Is No?

Magnetism is not a perfect proxy for “ferrous” and it should not be used as your only sorting rule. Many iron-based materials are magnetic, but some are not strongly magnetic in common conditions. Meanwhile, some non-ferrous metals can be magnetic. The main reason is that metals fall into different classes of magnetic behavior depending on their structure and composition, as explained in this overview of classes of magnetic materials.

Why Some Metals Are Magnetic A Practical Explanation?

In shop terms, magnetism comes from a material’s internal structure and how its atoms align under a magnetic field. You do not need the physics to make good decisions, but you do need the takeaway:

-

A material’s alloy family and microstructure can change whether it behaves magnetic.

-

Processing (like cold working) can shift that behavior for some alloys.

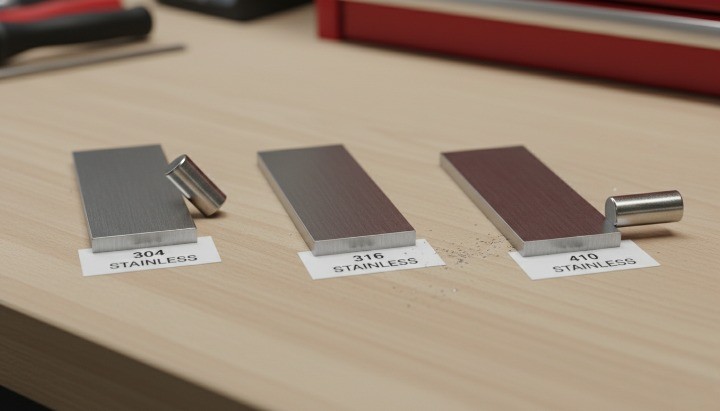

Why Ferrous Does Not Always Mean Magnetic Stainless Steel Nuances?

Stainless is ferrous (iron-based), but different stainless families behave differently:

-

Many ferritic and martensitic stainless steels are magnetic.

-

Many austenitic stainless steels are much less magnetic in the annealed state, and can become more magnetic after cold work.

If you are using a magnet to sort stainless, expect exceptions. If magnetism matters for function (not just sorting), validate the specific grade and condition.

Why Non Ferrous Does Not Always Mean Non Magnetic Nickel and More?

Nickel is a common counterexample: it is non-ferrous (not iron-based) and can be magnetic. Some nickel-containing alloys can also show magnetic response depending on structure and processing.

The practical point: non-ferrous is not a guarantee of “non-magnetic.”

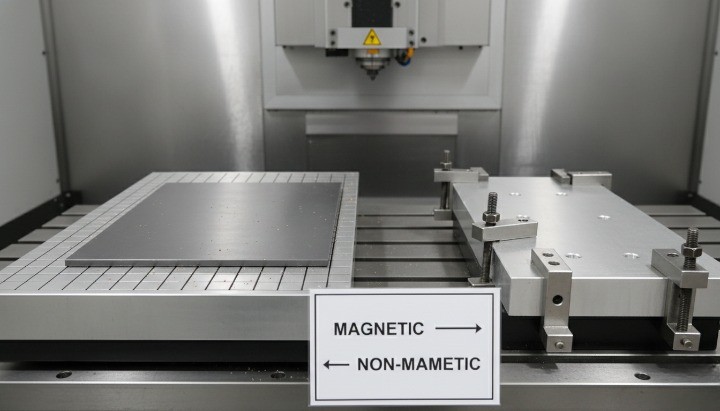

When magnetism affects CNC workholding and inspection?

Magnetism shows up in manufacturing more often than buyers expect:

-

Magnetic chucks / magnetic fixtures: great for flat ferrous plates; not an option for non-magnetic parts.

-

Chip control and cleanup: magnetic materials can be easier to clear with magnetic tools; non-magnetic swarf requires different housekeeping.

-

Inspection choices: some NDT methods, sorting steps, or part handling workflows assume magnetic response.

-

Assemblies near sensors: magnets can interfere with sensitive electronics or motion feedback systems.

If you have a “must be non-magnetic” constraint, include it in the RFQ and confirm it during prototyping.

Rust resistance comparison: rust vs corrosion

Rust is a specific kind of corrosion that happens to iron and steel. Corrosion can happen to many metals, including non-ferrous alloys. So the better question is not “does it rust?” but “how does it corrode in my environment, and what protection is realistic?”

Rust Is Iron Oxidation Corrosion Can Happen to Many Metals

When iron oxidizes in the presence of water and oxygen, it forms the familiar reddish-brown rust. That rust is porous and can keep growing, which is why bare carbon steel left outdoors can degrade quickly.

Non-ferrous metals do not form “red rust,” but they can still corrode:

-

Aluminum forms an oxide layer

-

Copper forms patina (often greenish)

-

Some environments cause localized corrosion (pitting, crevice corrosion)

Why Stainless Steel Does Not Rust Like Carbon Steel But Can Still Corrode?

Stainless steel uses chromium to form a protective surface film. That film improves resistance to general rusting compared to carbon steel.

But stainless is not “immune.” It can still corrode if:

-

Chlorides are present (common near salt or some process chemicals)

-

Crevices trap moisture and oxygen access is limited

-

Surface contamination or poor finishing disrupts the protective film

In other words: stainless reduces risk, but it does not remove the need to match grade + finish to the environment. For common grades and part types, these stainless steel machining parts examples show how material choice and finishing decisions work together in real CNC sourcing.

Aluminum and Copper Corrosion What to Expect?

Aluminum often performs well in many everyday environments because of its oxide film. Still, aluminum can pit in chloride exposure and can suffer when dissimilar metals create a galvanic couple. For cosmetic housings and outdoor exposure, anodizing parts can improve corrosion resistance and keep appearance more consistent when you specify the right type and sealing.

Copper and copper alloys have excellent corrosion behavior in many applications and are valued for conductivity. They can discolor and develop patina, which is acceptable in some products and unacceptable in cosmetic housings unless you coat or specify the surface finish.

Mixed Metal Assemblies and Galvanic Corrosion A Common Buyer Pitfall

If you bolt aluminum to stainless and add moisture, you can create a galvanic couple. The more “active” metal tends to corrode faster.

This shows up in real products as:

-

White corrosion products near fasteners

-

Pitting near contact points

-

Unexpected field failures even when each material “looks corrosion-resistant” alone

If your part will touch other metals, include that in your design review. Often a small change (coating, isolating washer, or material pairing choice) avoids the problem, and this kind of fastener and joint guidance is also covered in NASA’s Fastener Design Manual.

CNC Machinability What Changes Between Ferrous and Non Ferrous Metals

Machinability is mainly about how predictable the material is under a cutting tool: chip formation, heat, tool wear, burr behavior, and whether the surface finish stays stable across tool life. Ferrous vs non-ferrous gives you some broad trends, but grade and condition decide the outcome.

If you are comparing the machinability of ferrous metals specifically, the biggest practical variables are hardness/heat treat, work hardening tendency (common in many stainless grades), and abrasiveness (tool wear).

A Quick Machinability Map for Common CNC Alloys

Use this as a direction, not a promise:

-

Often easy / fast: many aluminum alloys, many brasses

-

Often stable but slower: many carbon steels

-

Often challenging: many stainless grades (work hardening), titanium alloys (heat management)

-

Special behavior: cast iron (abrasive + dust; great chip break), copper (gummy), magnesium (chip/fire risk planning)

The right tool geometry, coolant strategy, and feeds/speeds can shift these categories.

Ferrous machining notes: carbon steel, alloy steel, cast iron

Carbon steels often machine predictably. Depending on the grade and condition, they offer a good balance of cost, strength, and machinability.

Common CNC realities:

-

Tool wear is manageable, but increases with hardness and abrasiveness

-

Surface finish is usually stable when you control tool sharpness and vibration

-

Burrs are common on sharp edges and small features; plan for deburr

Alloy steels and heat-treated steels raise difficulty mainly through hardness and tool wear. When you ask for high strength, you often pay in cycle time and tool cost.

Cast iron behaves differently:

-

It often breaks chips easily (good for automation)

-

It can be abrasive; dust management and tool selection matter

-

It can deliver excellent damping for vibration-sensitive components

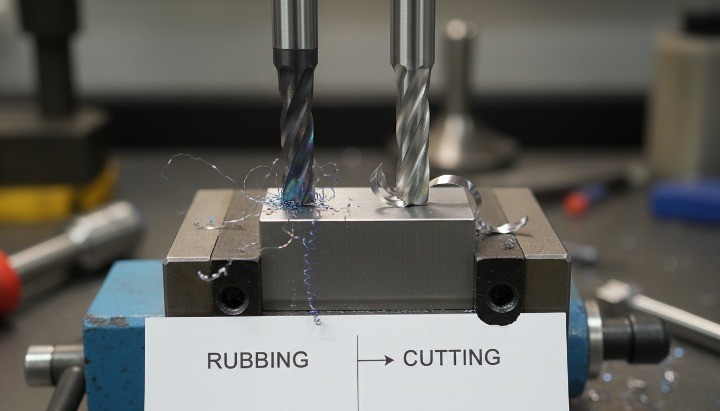

Stainless Steel Machining Work Hardening and Heat What to Control

Stainless is a frequent “why did this quote jump?” material. The challenges are usually:

-

Work hardening: the surface can get harder if you rub instead of cut

-

Heat concentration: poor heat conductivity can push heat into the tool

-

Built-up edge (BUE) and finish variation if the cut is not stable

Practical CNC controls include:

-

Keep tools sharp and use stable engagement

-

Avoid dwell and rubbing; maintain chip load

-

Use appropriate coolant strategy and tool coatings

If you have thin walls or deep pockets in stainless, plan for distortion and potentially additional operations.

Non Ferrous Machining Notes for Aluminum Brass and Copper

Aluminum is popular because it machines quickly and supports lightweight designs. The common CNC issues are not “can you cut it,” but:

-

Long chips in some alloys if chipbreak is not tuned

-

Burrs on small features

-

Surface finish variation if you get BUE (especially with dull tools or wrong cutting parameters)

When you want cleaner chip break and more stable surface finish on small precision components, many teams switch to brass. These brass parts examples show typical CNC brass applications where edge quality and repeatability matter.

Brass often machines extremely well with clean chip break and good surface finish. It’s a good choice for precision small parts when strength requirements fit and your application can accept the material and cost.

Copper can be “gummy.” It may smear, build up on tools, and require careful tool geometry and cutting strategy to keep the finish consistent. If conductivity is the driver, plan extra attention to process control and surface requirements.

Special Non Ferrous Metals Titanium and Magnesium Risks and Planning

Titanium brings strength and corrosion resistance but is not a “fast machining” material. Heat management and tool life are the core constraints, and thin features can move if your workholding is not rigid.

Magnesium can machine very fast, but chip and dust handling require a safety plan. If magnesium is on the table, align early on coolant strategy, chip collection, and shop controls.

DFM Cheat Sheet How Material Properties Affect CNC Results

Below is a practical table to connect “family-level properties” to what you actually see in CNC production.

| Material family (examples) | Typical magnetic behavior | Rust / corrosion behavior | CNC machinability notes | Common CNC part examples | Practical tips for RFQ/DFM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon steel (low/alloy carbon steels) | Usually magnetic | Will rust if unprotected | Predictable; moderate speeds; deburr needed | Brackets, shafts, fixtures | Specify coating/finish if exposed; call out heat treat if required |

| Stainless steel (varies by grade) | Varies by family and condition | Better rust resistance; can still corrode in harsh environments | Can work harden; manage heat; stable chip load | Fasteners, housings, food/medical parts | Specify grade + condition; define environment (chlorides, cleaning chemicals) |

| Cast iron | Usually magnetic | Can oxidize; often coated/painted | Abrasive; good chip break; dust handling | Machine bases, housings | Define surface finish zones; plan for dust and post-cleaning |

| Aluminum alloys | Non-ferrous; generally non-magnetic | No red rust; can pit; galvanic risk | Fast machining; watch BUE, burrs, thin-wall distortion | Plates, enclosures, heat sinks | Specify alloy/temper; include anodize or coating needs; note mating metals |

| Brass/bronze (copper alloys) | Non-ferrous; generally non-magnetic | Good corrosion behavior; can tarnish | Often excellent chip control; good finish | Bushings, fittings, precision parts | Define cosmetic requirements; confirm any lead-free restrictions if applicable |

| Copper | Non-ferrous; generally non-magnetic | Corrodes/patinates; environment-dependent | Can smear; tool selection matters | Electrical/thermal parts | Specify finish requirements; protect surfaces for conductivity/cosmetic needs |

| Titanium alloys | Non-ferrous; generally non-magnetic | Excellent corrosion resistance in many environments | Slower machining; heat/tool life drives cost | Medical, aerospace, chemical | Expect longer cycle time; define critical features and inspection early |

Carbon Steel vs Aluminum Cost Why Total Cost Can Flip?

Carbon steel vs aluminum cost is not just a price-per-pound comparison. In CNC parts, total cost often depends more on machining time, tool life, finishing, and scrap risk than on the raw stock line item.

Raw material vs machining time vs finishing

Common cost drivers that make aluminum cheaper or more expensive than expected:

-

Cycle time: aluminum often supports higher cutting speeds, which can reduce machining time.

-

Tool life and tool cost: harder ferrous materials can increase wear; some stainless/titanium cases are tool-life limited.

-

Finishing: carbon steel often needs plating/paint/powder coat to prevent rust; aluminum may need anodize for corrosion and cosmetics.

-

Tolerance and distortion: thin aluminum walls can move; heat-treated steels may require extra steps; stainless can be sensitive to process.

The result: an aluminum part can be more expensive than a steel part even if the aluminum stock is cheaper, or vice versa.

Weight, shipping, and handling

If you ship parts internationally or in high volume, weight matters. Aluminum can reduce:

-

Shipping cost

-

Handling effort

-

In-use weight (which can be valuable for equipment performance)

But weight alone shouldn’t drive the decision if corrosion, stiffness, or wear are the dominant requirements.

Common quoting mistakes to avoid

If you want comparable quotes, avoid these pitfalls:

-

Leaving the material callout vague (“steel” or “aluminum” with no grade/condition)

-

Not specifying finishing and corrosion expectations

-

Not disclosing the real environment (salt, chemicals, outdoor exposure)

-

Mixing cosmetic and functional surfaces without clearly marking them on drawings

How to Choose the Right Metal for Real Parts Common Use Cases?

Start with the part’s job (load, environment, assembly, finish), then choose the material family, then pick the grade and process. Here are common patterns we see in CNC sourcing.

Brackets and plates

For brackets, plates, and structural supports:

-

If stiffness and cost are primary: carbon steel is common, with a protective coating if exposed.

-

If weight and corrosion resistance matter: aluminum is common, often with anodize or powder coat for durability and cosmetics.

If you use magnetic workholding for plate machining, ferrous materials can simplify fixturing, while aluminum requires mechanical clamping or vacuum strategies.

Shafts, pins, and wear surfaces

For shafts and wear points:

-

Ferrous alloys often make sense because they support heat treat and wear resistance strategies.

-

Non-ferrous options can work when corrosion or weight is more important, but confirm wear behavior.

If the design includes press fits or tight bearing seats, consider how finishing (plating, anodize) changes dimensions and how you will inspect critical diameters.

Housings and Enclosures Corrosion Resistance and Aesthetics

For housings:

-

Aluminum is common for weight and corrosion behavior, plus anodize options.

-

Stainless is chosen when the environment is harsh and you need long-term durability, but plan for higher machining cost.

-

Carbon steel can work if you control coating and sealing.

In mixed-metal assemblies, proactively address galvanic risk and fastener selection.

Metal Choice for Electrical and Thermal Parts

If conductivity or heat transfer is key:

-

Copper and aluminum are common choices.

-

Surface condition and plating can matter for contact resistance.

Confirm what “surface finish” means functionally (conductive contact vs cosmetic appearance) before you lock the process.

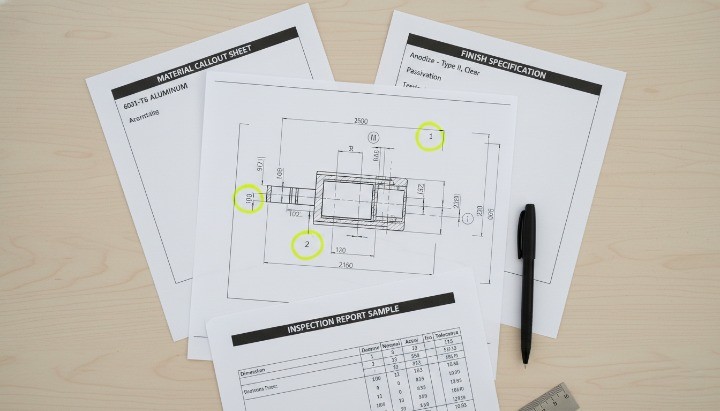

RFQ Checklist So Your CNC Quotes Are Comparable

If you want clean pricing and fewer engineering loops, include these items in your RFQ package.

Material callout details that matter

-

Alloy/grade + condition (avoid “steel” or “aluminum” alone)

-

Product form if it matters (bar/plate/tube/forging/casting)

-

Any required heat treat or mechanical property requirement (if you have it)

If magnetism matters, add it as a requirement and confirm how you will validate it.

Environment and Finishing Details That Matter Most

-

Indoor/outdoor, humidity, salt exposure, chemicals, temperature cycling

-

Desired appearance and durability (paint, plating, anodize, passivation, etc.) — see our surface treatment options for practical finish choices by environment and cosmetic goals

-

Whether the part contacts other metals (galvanic risk)

Finishing changes dimensions. If you have tight fits, define which surfaces are critical and how finishing will be handled.

Inspection notes that reduce risk

-

Mark critical-to-function dimensions and datums

-

Call out surface finish requirements where they truly matter

-

Define how threads, fits, and key features will be verified (gaging, CMM, etc.)

These details help avoid “quote looks good, but production surprises show up later.”

FAQ

Are all ferrous metals magnetic?

No. Many iron-based materials are magnetic, but some stainless steels can be weakly magnetic in certain conditions and may change after processing. If magnetism matters, validate the specific grade and condition.

Do non-ferrous metals rust?

They don’t form red iron rust, but non-ferrous metals can still corrode (oxidize, pit, tarnish, or corrode galvanically).

Is stainless steel ferrous or non-ferrous?

Stainless steel is ferrous because it is iron-based. “Stainless” describes its corrosion behavior compared to carbon steel, not whether it contains iron.

Which is easier to machine: steel or aluminum?

Often aluminum machines faster, but “easier” depends on the alloy and the features. Many carbon steels machine predictably; some stainless and titanium cases are more challenging because of heat and tool wear.

How should I specify material for CNC parts?

Specify alloy/grade + condition, plus finishing and environment. If you only write “steel” or “aluminum,” you will get apples-to-oranges quotes and higher risk of rework.

Conclusion

Ferrous vs non-ferrous is a useful first filter, but your best outcome comes from matching magnetic behavior, corrosion risk, and machinability to the part’s real job and environment. When you specify grade, condition, finishing, and inspection expectations clearly, you reduce quote noise and prevent expensive surprises in production.

If you’re choosing between steel, stainless, aluminum, or another alloy for a CNC part, send your drawing and operating environment via our contact for a quote page. We can suggest a practical material + finishing plan and quote with clear assumptions.